Google Adds Graffiti to Its Art Portfolio

Featured on nytimes.com

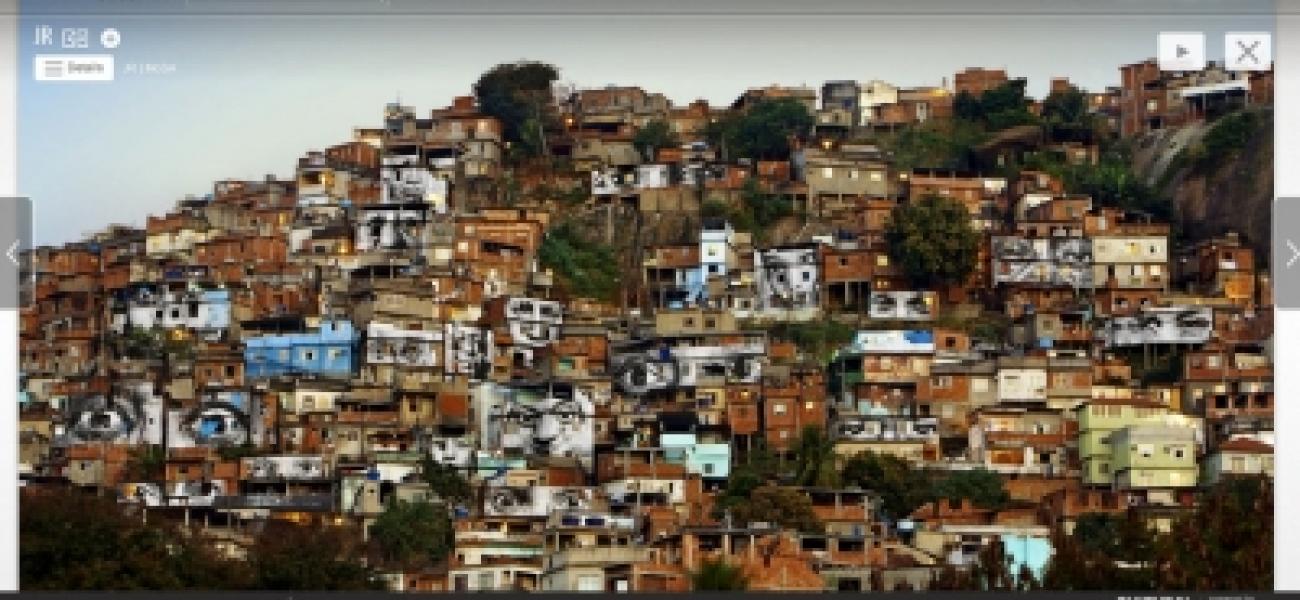

There’s a portrait of an anonymous Chinese man chiseled into a wall in Shanghai, a colorful mural in Atlanta and black-and-white photographs of eyes that the French artist JR affixed to the houses of a hillside favela in Rio de Janeiro. These are among the images of more than 4,000 works included in a vast new online gallery of street art that Google is unveiling here on Tuesday.

Called the Street Art Project, the database was created by the company’s Paris-based Google Cultural Institute. Using images provided by cultural organizations worldwide, some of which were captured with Google’s Street View camera technology, it includes street art from around the globe, including work that no longer exists, like the 5Pointz murals in Long Island City, Queens, or the walls of the Tour Paris 13 tower in France.

With the initiative, Google is the latest organization to wade into debates about how or whether to institutionalize, let alone commercialize, art that is ephemeral and often willfully created subversively. A private database of public art, it also poses questions about how to legally preserve what in some cases might be considered vandalism.

In a sense, Google is formalizing what street art fans around the world already do: take pictures of city walls and distribute them on social media. Yet for Google to do so could raise concerns, given the criticism of its aggressive surveillance tactics, especially in Europe, where its Street View satellite mapping is widely seen as a violation of privacy.

Google is taking pains to avoid offense by setting strict conditions. It will include only images provided by organizations that sign a contract attesting that they own the rights to them. It will not cull through Street View images but will provide the technology to organizations that want to use it to record street art legally. Some groups have provided exact locations of the artworks; others have not.

Aiming to steer clear of one of the most contentious debates in the street art world, Google says it will not include images from groups seeking to sell the art or images of it. Many street artists object to their public work being sold without their permission. For instance, Banksy, the anonymous British street artist, has objected to attempts to sell his artworks after they are stripped from public walls, saying the stencils belong to the community.

Google also said it would remove images if artists complained to the groups that contributed them to the database.

The company sees the platform as a way of making more art available to viewers. “I’m not treating street art as anything different from what I would do with the Impressionist collection I’m getting on Art Project,” said Amit Sood, director of the Google Cultural Institute, referring to a philanthropic initiative that has provided technical support to more than 460 museums to help put their collections online.

The institute, which was founded in 2011 and has a staff of around 30 engineers, has also helped create online archives for historic figures likeNelson Mandela and used Street View to provide multimedia renderings of Unesco World Heritage sites like Angkor Wat in Cambodia.

Mr. Sood acknowledges that the street art program, like the Cultural Institute, is a way for Google to generate good will in privacy-conscious Europe. “It helps make people realize we are doing a lot of things that actually support the community,” he said.

The database is searchable by artist, city, genre and other categories, and even includes a special section on New York walls of the 1990s. Among the 30 institutions that have furnished images so far are the Museum of the City of New York; the Dallas Contemporary exhibition space in Texas; The City Speaks in Atlanta, which finances street art and disseminates it online; and the Museum of Street Art in France.

Working with the French organization Project Tour Paris 13, Google filmed the rooms of Tour 13 in Paris, which had been entirely covered in street art, before its owners destroyed the building. Google also used a powerful camera to capture works by the Portuguese graffiti artist Vhils, who uses an electric chisel to carve images into the sides of buildings. Viewers can zoom in on the chisel marks.

Shepard Fairey, who is best known for his image of President Obama, said he had “no problem” with being included in the database. “I’ve always used my street art to democratize art, so it would be philosophically inconsistent for me to protest art democratization through Google,” he said through a publicist. And the Belgian artist known as ROA said he would be pleased to be part of it, “as long as they credit the mural to me, and it’s not being used for commercial purposes or corporations.”

Some past attempts to institutionalize street art have not gone over so well. The police commissioner of Los Angeles criticized a 2011 exhibition called “Art in the Streets” at that city’s Museum of Contemporary Art, arguing that it encouraged vandalism.

Click here to read the full article.