Mark Rothko on How to Be an Artist

ARTSY EDITORIAL, BY ALEXXA GOTTHARDT

Famed Abstract Expressionist Mark Rothko believed that art was a powerful form of communication. “The fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I can communicate those basic human emotions,” he said in an interview in 1956. “The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them.”

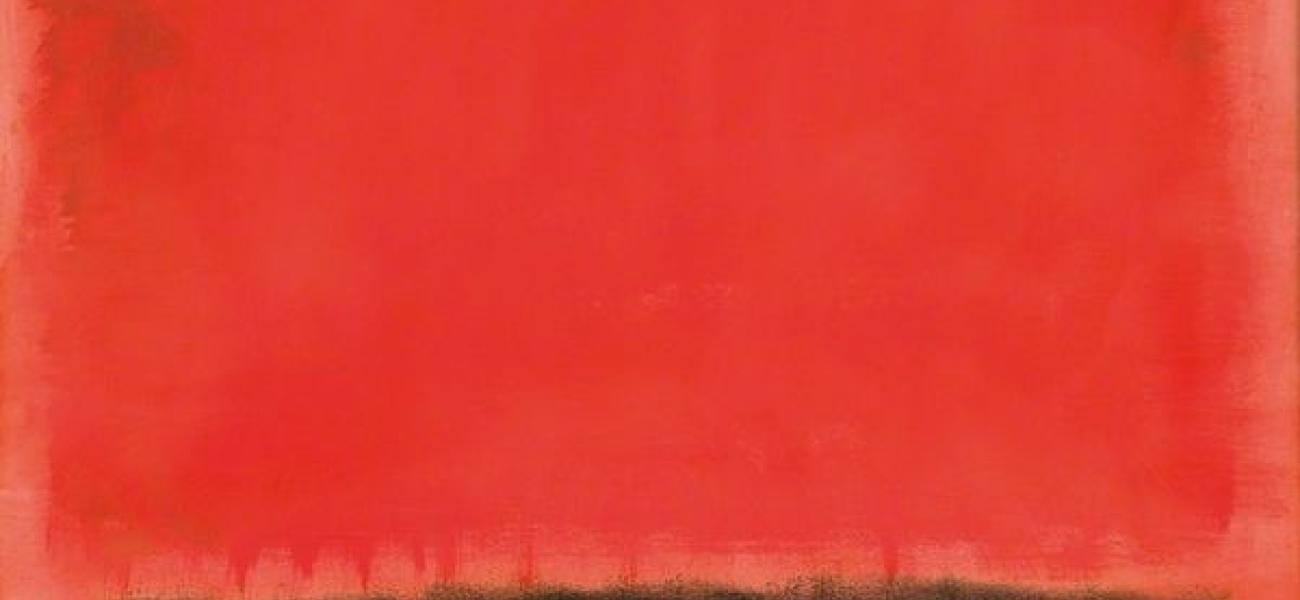

Through canvases of floating forms and glowing, suspended rectangles, Rothko sought to create a profound connection between artist, canvas, and viewer. What’s more, he asserted that his works not only expressed human emotion, but also stimulated psychological and emotional experiences in those who witnessed them. “Painting is not about an experience,” he told LIFE magazine in 1959. “It is an experience.”

While Rothko believed his paintings spoke for themselves—and routinely derided art critics who attempted to explain his practice with words—that didn’t stop him from developing his own theories about the power of art and the creative process. Throughout his career, from the late 1920s until his death in 1970, the New York–based painter amassed a body of writing and gave a number of interviews that reveal his views on how creativity can be unlocked and encouraged. Below, we highlight several of Rothko’s words of wisdom.

Follow your childlike instincts

In one of Rothko’s earliest essays, “New Training for Future Artists and Art Lovers” (1934), the artist emphasized the creative benefits of approaching art like a child might—instinctively, without the guidelines of overbearing instruction. By watching children work, he wrote, “you will see them put forms, figures, and views into pictorial arrangements, employing of necessity most of the rules of optical perspective and geometry, but without the knowledge that they are employing them.” This may be why, he wrote, “their paintings are so fresh, so vivid and varied.” He added that an artist of any skill level should seek to “make his work arresting and provoking of attention.”

What’s more, Rothko advised artists to naturally express emotions and experiences, like children do, in order to develop their own unique style. “As a result of this method,” he wrote, “each child works on his own idea, and actually develops a style of his own whereby his work is distinguishable from everyone else’s.”

Rothko would develop these innovative pedagogical theories throughout his adult life, focusing on art instruction that supports each individual artist’s instincts, rather than limiting their creative impulses by pushing general principles. In one manuscript, which he wrote around 1941 while serving as art supervisor at the Center Academy of the Brooklyn Jewish Center, he called for “avoidance of physical and emotional inhibitions” in teaching. He applied these ideas to his own practice, too. Rothko dug deep into his own subconscious in order to free himself from what he saw as the restrictive nature of representation. Eventually, this process fueled the abstract paintings that would define his groundbreaking practice and pioneer Color Field Painting.

Express the inexpressible

Rothko came of age at a time when painters itched to break completely from the confines of representation. Building on forays into abstraction pioneered by their modernist predecessors, like Wassily Kandinsky, Rothko and his fellow Abstract Expressionists wanted to remove all allusions to the physical world in their work. Instead, their paintings would embody metaphysical forces and interior worlds. As art critic David Cotner put it, Rothko “used colors, shades and gestures as moving evocations of mythology itself.”

Indeed, Rothko emphasized that “the most interesting painting is one that expresses more of what one thinks than of what one sees.” Likewise, he placed great weight on abstraction’s ability to convey what is most important to humans—not the world around them, but their emotional life. “[Shapes] have no direct association with any particular visible experience, but in them, one recognizes the principle and passion of organisms,” he wrote, in the art journal Possibilities.

While Rothko was a master colorist, as evidenced by his signature monochromatic rectangles, whose deep reds and blacks reverberated against each other, he routinely emphasized that his paintings weren’t simply about a selective palette. “If you are only moved by color relationships, you are missing the point,” he once told writer Selden Rodman. “I am interested in expressing the big emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on.” He believed that these emotions, when conveyed through abstraction, would stoke intimate, profound emotional experiences in the viewer, as well. “One does not paint for design students or historians but for human beings,” Rothko stressed to curator William C. Seitz, “and the reaction in human terms is the only thing that is really satisfactory to the artist.”

Eliminate barriers between audience and canvas

To achieve this deep and direct response from viewers, Rothko took care to remove what he saw as “obstacles between the painter and the idea, and between the idea and the observer,” as he said in a statement published in the art journal Tiger’s Eye in 1949. He wanted to forge clear pathways through which his audience could fully experience his paintings, which became, as scholar Miguel Lopez-Remiro has pointed out, “scene[s] of communication with the viewer.”

He achieved this through increasingly abstract compositions, lacking identifiable markers of the outside world. He also left his paintings untitled, allowing viewers to respond to the forms that filled them, rather than written clues. Rothko gravitated towards large canvases without frames, too, so that the work became one with the audience’s environment—as interactive as a door or window might be. “Small pictures since the Renaissance are like novels,” he once said in a lecture at Pratt Institute. “Large pictures are like dramas in which one participates in a direct way.”

The painter also advised that viewers situate themselves as close as 18 inches away from his canvases, “perhaps to dominate the viewer’s field of vision and thus create a feeling of contemplation and transcendence,” as the Museum of Modern Art has suggested.

Remove ego from your art

Rothko also identified the artist’s ego as a major roadblock in facilitating a meaningful connection between artwork and audience. He believed that ego, or allusions to the artist’s biography and role in society, only distracted from art’s true power to elicit “pure human reactions.”

While Rothko embedded his own emotions into his abstractions, he believed these were universal elements of the human experience, not unique to his situation. “I don’t express myself in my paintings,” he once whispered to critic Harold Rosenberg, while waxing on Abstract Expressionism at a party. “I express my not-self.”

The most poignant example of Rothko’s intent to remove ego from art is his theoretical manuscript “The Artist’s Reality,” which was published by his family in 2004, long after the artist’s 1970 suicide (Rothko suffered from depression throughout his adult life). While the text presents many of Rothko’s most developed theories on art and creativity, he very rarely uses the word “I,” and doesn’t mention his own paintings or practice. Indeed, his transcendent abstractions, too, are absent of any “I.” Instead, they express emotions that are universally understood and experienced by humans.