The Dodo's Last Gleaming

"The Dodo's Last Gleaming"

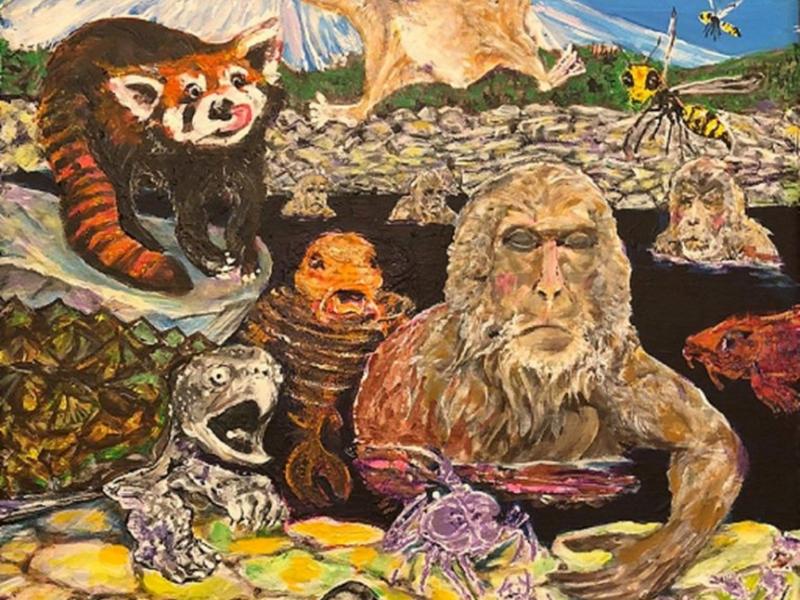

This painting depicts one of the last Dodo birds

watching his fate unfold before him.

The Dodo, (Raphus cucullatus), is an extinct flightless bird of Mauritius, an island of the Indian Ocean; It is one of the three species that constituted the family Raphidae, usually placed with pigeons in the order Columbiformes but sometimes separated as an order (Raphiformes).

The other two species, also found on islands of the Indian Ocean, were the solitaires (Raphus solitarius of Réunion and Pezophaps solitaria of Rodrigues).

The birds were first seen by Portuguese sailors about 1507 and were exterminated by humans and their introduced animals. The dodo was extinct by 1681, the Réunion solitaire by 1746, and the Rodrigues solitaire by about 1790.

The dodo is frequently cited as one of the most well-known examples of human-induced extinction and also serves as a symbol of obsolescence with respect to human technological progress.

It’s commonly believed that the dodo went extinct because Dutch sailors ate the beast to extinction after finding that the bird was incredibly easy to catch due to the fact it had no fear of humans, (why it didn’t fear the creature many times its size is a mystery for another day).This is, for the for the most part, pretty accurate.

It is noted that after sailors landed and settled on the island in 1598, the dodo’s population rapidly declined and other sources confirm that the dodo was indeed hunted by sailors looking for an easy snack, since the dodo’s ungainly gait and lack of a third axis of movement made it relatively easy to catch.

However, in a report released by the Oxford University of Natural History, it’s the animals the sailors brought with them that are named as one of the key reasons our hapless feathery friend saw his demise. Pigs, dogs and rats are all animals said to have developed a taste for dodo eggs; this introduction of such animals into a foreign ecosystem, combined with humans hunting and eating them, saw the delicate balance the dodo had enjoyed for so long destroyed. The species was soon cripplingly endangered. And as a result, it faded from existence.

The dodo was bigger than a turkey, and weighed about 50 pounds.

It had blue-gray plumage, a big head, a 9-inch blackish bill with a reddish sheath forming the hooked tip, small useless wings, stout yellow legs, and a tuft of curly feathers high on its rear end.

The Réunion solitaire may have been a white version of the dodo.

The brownish Rodrigues solitaire was taller and more slender, with smaller head, short bill lacking the heavy hook, and wings with knobs.

All that remains of the dodo is a head and foot at Oxford, a foot in the British Museum,

a head in Copenhagen, and skeletons, more or less complete, in various museums of Europe, the United States, and Mauritius.

Many bones of solitaires have also been preserved.

The dodo’s prominent role in bringing attention to the extinction of species,

coupled with advances in genetics that could allow for its resurrection (de-extinction),

have led scientists to consider the possibility of bringing the dodo back.

The sequencing of the dodo genome by geneticists in 2016 reinvigorated this discussion as well as the ethical debate of using de-extinction techniques to alter natural history.